A mysterious example of ancient Greek graffiti may reveal the existence of a lost temple at the iconic Acropolis of Athens, a pair of researchers have proposed in a study.

The Acropolis—an ancient citadel that sits atop a rocky outcrop overlooking the Greek capital—is one of the most visited and well-known archaeological sites in the world. The site is dominated by the ruins of the Parthenon, a marble temple dedicated to the goddess Athena—built in 5th century B.C.—that has become emblematic of ancient Greece.

But despite its renown, researchers are still uncovering new insights into the history of the Acropolis. A study published in the American Journal of Archaeology (AJA), for example, proposes that graffiti found outside Athens possibly depicts an archaic temple in the ancient citadel that predates the Parthenon.

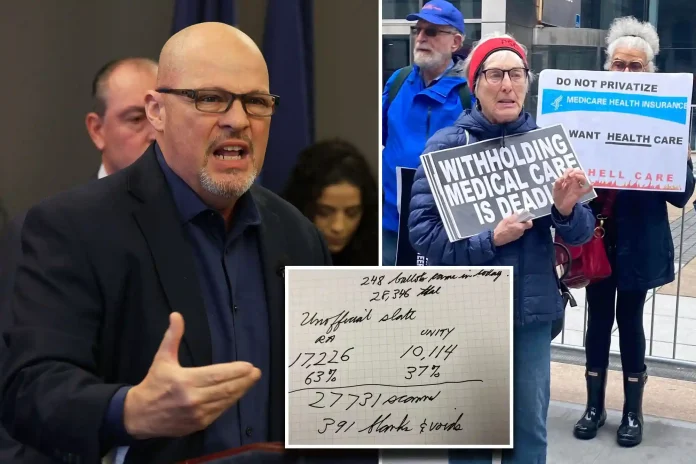

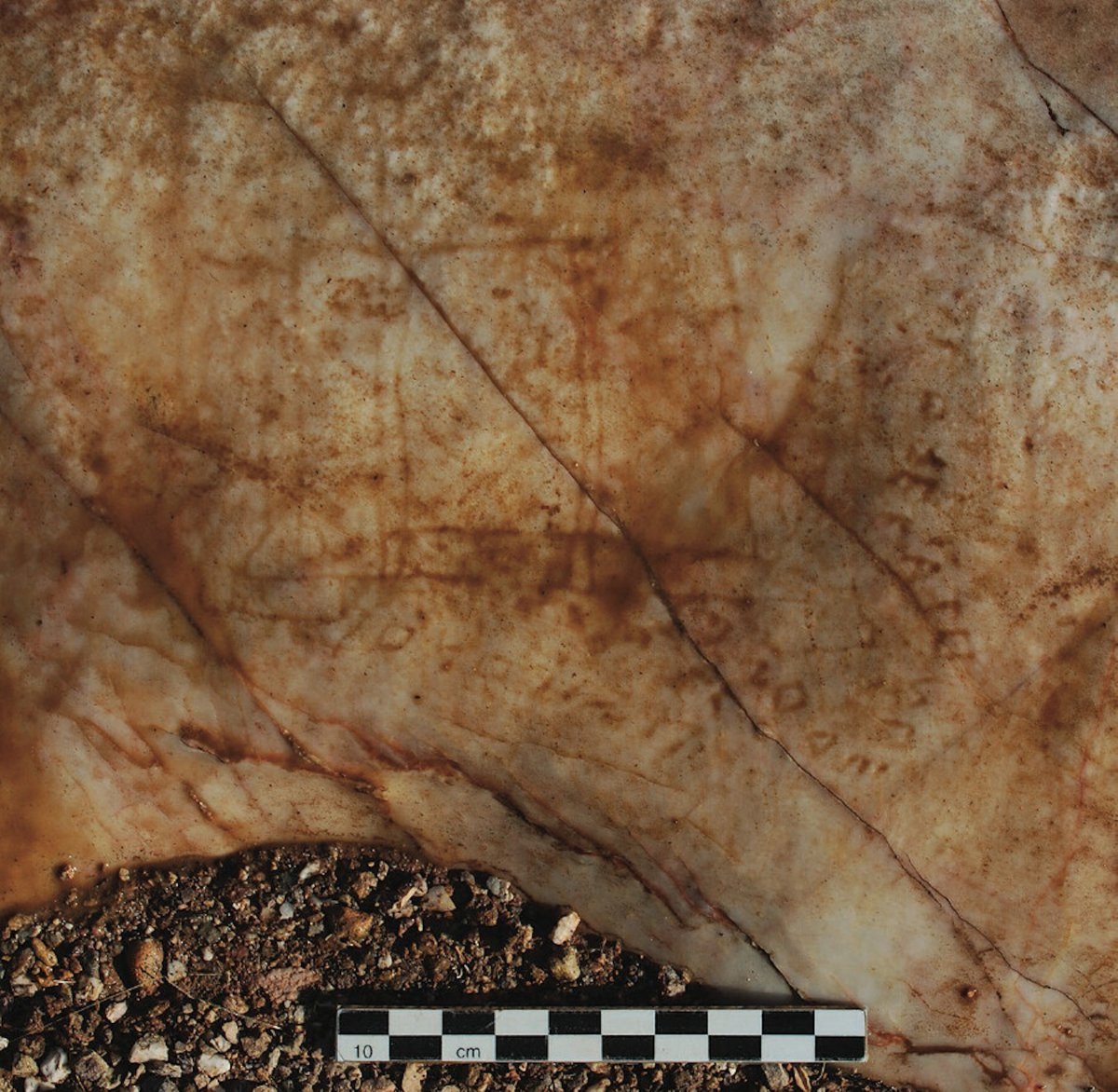

The tiny graffiti—which consists of a “remarkable” engraving of a building—was found on a marble rock outcrop at Barako Hill near Vari, around 12 miles southeast of Athens in Greece’s Attica region.

“The inscription [beside the engraving] does not mention the Acropolis of Athens, and so, as we indicate in the article, there is always a margin of uncertainty about the identity of the building. However, that the drawing refers to the Acropolis seems, on current evidence, probable to us,” Janric van Rookhuijzen, classical archaeologist and author of the AJA study with Radboud University in the Netherlands, told Newsweek.

The engraving is among more than 2,000 examples of graffiti that have been found on marble outcrops in the hills north and east of Vari. The graffiti has been documented in recent years by researcher Merle Langdon of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville—the other author of the AJA study.

This “extraordinary” concentration of graffiti typically consists of simple drawings (including animals, buildings, erotic scenes, ships and warriors) or short inscriptions (including captions, messages and names) written in a very ancient version of the Greek alphabet. The shapes of the letters indicate that this graffiti is dated to 6th century B.C.

In many cases, creators of the engravings identity themselves as shepherds and goatherds. Why these people took the time to produce these drawings is not known, but perhaps they were simply trying to alleviate the monotony of their daily work.

The graffiti carved into a rock on Barako Hill appears to have been created by an individual—likely a shepherd or goatherd—who identifies himself as “Mikon,” according to an inscription that accompanies the drawing.

“Merle Langdon found the engraving by chance as far back as 2003,” van Rookhuijzen said. “He was looking closely at all rock surfaces on Barako Hill, trying to find the word [for] “boundary” in his belief that the hill is a perfect natural boundary between two Attic demes.” (In ancient Attica, “demes” were administrative subdivisions of land.)

While several details of Mikon’s engraving are not fully understood, it appears to depict a colonnaded building, most likely a temple, according to the study. This structure is identified by the inscription as “the Hekatompedon.”

This term is significant because in ancient Greek, it means “100-footer”—referring to a structure of enormous size. The use of the definite article “the” implies that a specific building was depicted, most probably on the Acropolis of Athens, the researchers propose.

One factor supporting this hypothesis is that the distance between the graffiti and the Acropolis is only around 12 miles. Moreover, the Acropolis is already visible from Mount Hymettos, which is even closer to the graffiti.

In addition, “the Hekatompedon” term is known to have been the official ancient name of the temple dedicated to Athena at the Acropolis that later became known as the Parthenon.

But construction of the Parthenon is not thought to have begun until around 450 B.C.—whereas the graffiti dates to 6th century B.C. As a result, the researchers suggest the drawing could refer to a building that stood at the Acropolis prior to construction of the Parthenon.

It has long been suspected that the Acropolis was home to temples even older than the Parthenon. But the appearance, age and exact locations of such structures have been the subject of fierce debate.

Hindering our understanding of these archaic temples is the fact that in 480 B.C., the buildings that then stood on the Acropolis were destroyed by a Persian army that had attacked Athens.

Having been created long before this event—and the construction of the Parthenon—Mikon’s graffiti “is unique for possibly offering a window on the earlier incarnation of the Acropolis, which no longer exists,” van Rookhuijzen said. “We have nothing else like this.”

“What is more: from an official Athenian decree dating to 485/4 B.C., it has long been known that there was something called the Hekatompedon on the old Acropolis before the arrival of the Persians. But there is much discussion as to what the Hekatompedon was,” he said.

Some scholars already think that the Hekatompedon was a temple. But other scholars rule out that the neuter term “the Hekatompedon” can refer to a temple building in ancient Greek—arguing that, instead, it would have been something like an open courtyard.

“The newly published graffito [sometimes used as the singular noun of graffiti], which combines the neuter term with a drawing of what is most likely a temple building, promotes the view that the Hekatompedon on the old Acropolis was a temple after all,” van Rookhuijzen said.

“The graffito is also significant because it attests to early literacy, as well as an interest in architecture, among the rural population of Attica.”